How To Start New Habits That Actually Stick

Nov 1, 2021

The Science of How Habits Work

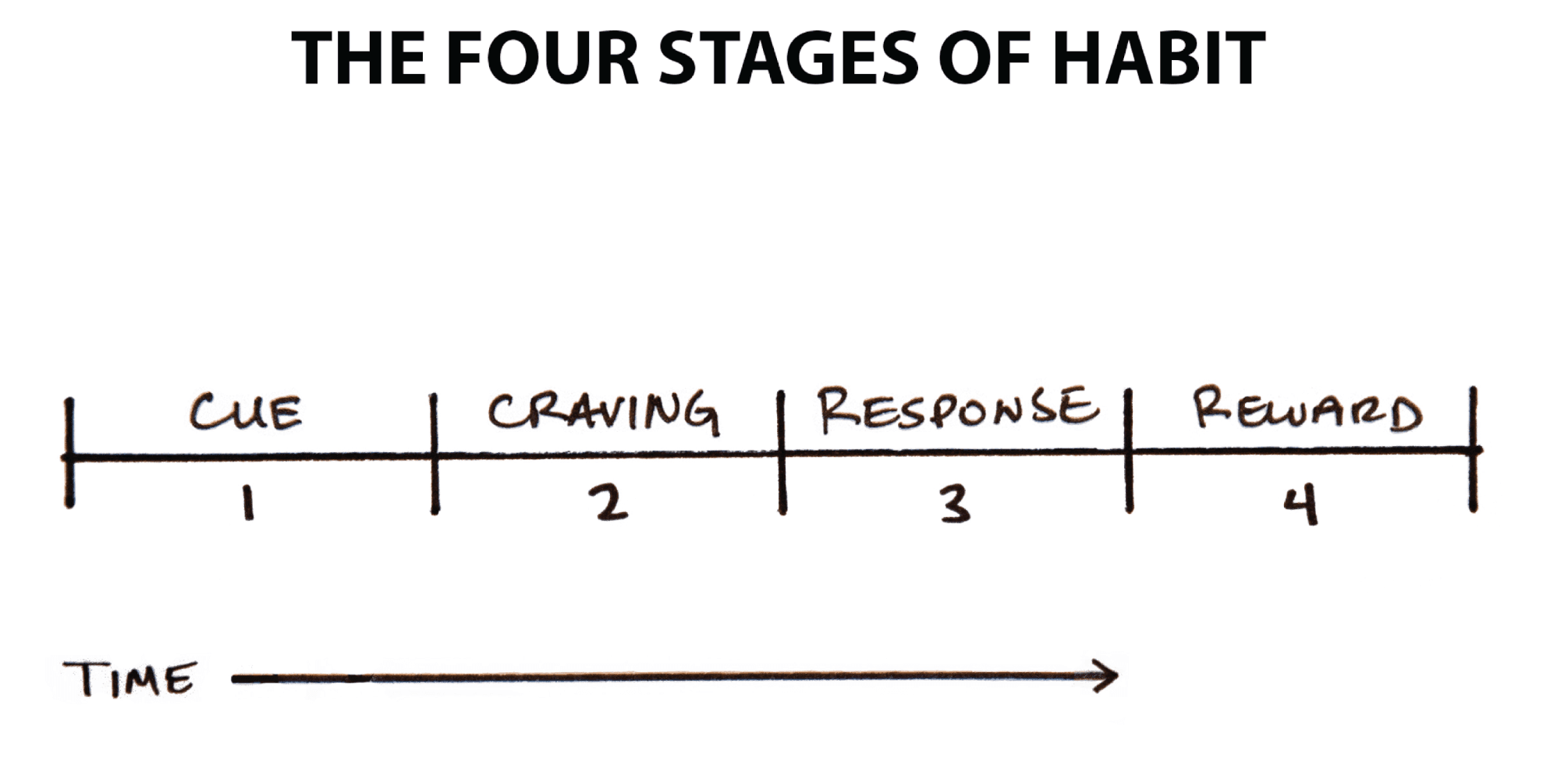

The process of building a habit can be divided into four simple steps: cue, craving, response, and reward.

Breaking it down into these fundamental parts can help us understand what a habit is, how it works, and how to improve it.

All habits proceed through four stages in the same order: cue, craving, response, and reward.

This four-step pattern is the backbone of every habit, and your brain runs through these steps in the same order each time.

First, there is the cue. The cue triggers your brain to initiate a behavior. It is a bit of information that predicts a reward. Our prehistoric ancestors were paying attention to cues that signaled the location of primary rewards like food, water, and sex. Today, we spend most of our time learning cues that predict secondary rewards like money and fame, power and status, praise and approval, love and friendship, or a sense of personal satisfaction. (Of course, these pursuits also indirectly improve our odds of survival and reproduction, which is the deeper motive behind everything we do.)

Your mind is continuously analyzing your internal and external environment for hints of where rewards are located. Because the cue is the first indication that we’re close to a reward, it naturally leads to a craving.

Cravings are the second step of the habit loop, and they are the motivational force behind every habit. Without some level of motivation or desire—without craving a change—we have no reason to act. What you crave is not the habit itself but the change in state it delivers. You do not crave smoking a cigarette, you crave the feeling of relief it provides. You are not motivated by brushing your teeth but rather by the feeling of a clean mouth. You do not want to turn on the television, you want to be entertained. Every craving is linked to a desire to change your internal state. This is an important point that we will discuss in detail later.

Cravings differ from person to person. In theory, any piece of information could trigger a craving, but in practice, people are not motivated by the same cues. For a gambler, the sound of slot machines can be a potent trigger that sparks an intense wave of desire. For someone who rarely gambles, the jingles and chimes of the casino are just background noise. Cues are meaningless until they are interpreted. The thoughts, feelings, and emotions of the observer are what transform a cue into a craving.

The third step is the response. The response is the actual habit you perform, which can take the form of a thought or an action. Whether a response occurs depends on how motivated you are and how much friction is associated with the behavior. If a particular action requires more physical or mental effort than you are willing to expend, then you won’t do it. Your response also depends on your ability. It sounds simple, but a habit can occur only if you are capable of doing it. If you want to dunk a basketball but can’t jump high enough to reach the hoop, well, you’re out of luck.

Finally, the response delivers a reward. Rewards are the end goal of every habit. The cue is about noticing the reward. The craving is about wanting the reward. The response is about obtaining the reward. We chase rewards because they serve two purposes: (1) they satisfy us and (2) they teach us.

The first purpose of rewards is to satisfy your craving. Yes, rewards provide benefits on their own. Food and water deliver the energy you need to survive. Getting a promotion brings more money and respect. Getting in shape improves your health and your dating prospects. But the more immediate benefit is that rewards satisfy your craving to eat or to gain status or to win approval. At least for a moment, rewards deliver contentment and relief from craving.

Second, rewards teach us which actions are worth remembering in the future. Your brain is a reward detector. As you go about your life, your sensory nervous system is continuously monitoring which actions satisfy your desires and deliver pleasure. Feelings of pleasure and disappointment are part of the feedback mechanism that helps your brain distinguish useful actions from useless ones. Rewards close the feedback loop and complete the habit cycle.

If a behavior is insufficient in any of the four stages, it will not become a habit. Eliminate the cue and your habit will never start. Reduce the craving and you won’t experience enough motivation to act. Make the behavior difficult and you won’t be able to do it. And if the reward fails to satisfy your desire, then you’ll have no reason to do it again in the future. Without the first three steps, a behavior will not occur. Without all four, a behavior will not be repeated.

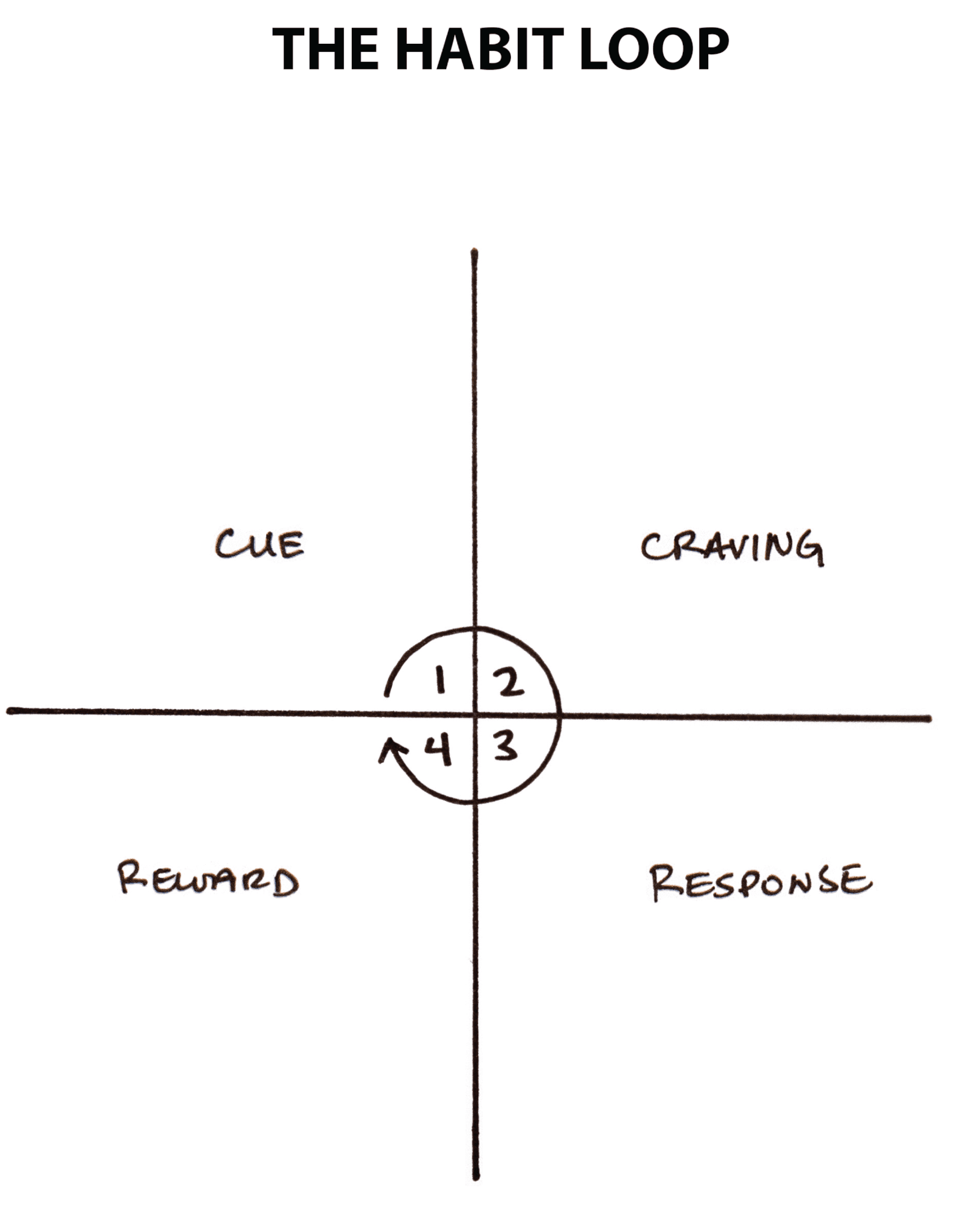

The four stages of habit are best described as a feedback loop. They form an endless cycle that is running every moment you are alive. This “habit loop” is continually scanning the environment, predicting what will happen next, trying out different responses, and learning from the results. Charles Duhigg and Nir Eyal deserve special recognition for their influence on this image. This representation of the habit loop is a combination of language that was popularized by Duhigg’s book, The Power of Habit, and a design that was popularized by Eyal’s book, Hooked.

In summary, the cue triggers a craving, which motivates a response, which provides a reward, which satisfies the craving and, ultimately, becomes associated with the cue. Together, these four steps form a neurological feedback loop—cue, craving, response, reward; cue, craving, response, reward—that ultimately allows you to create automatic habits.

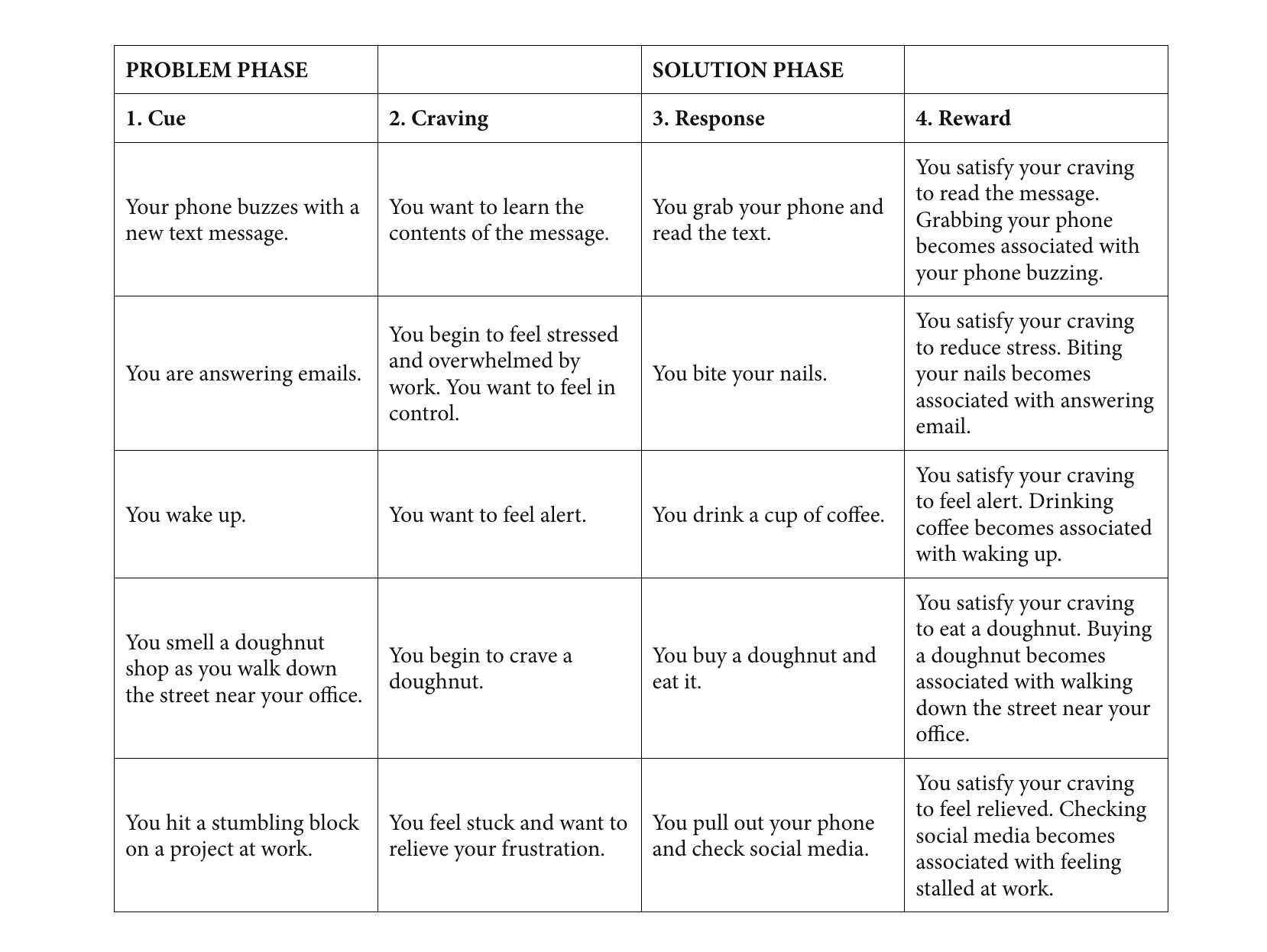

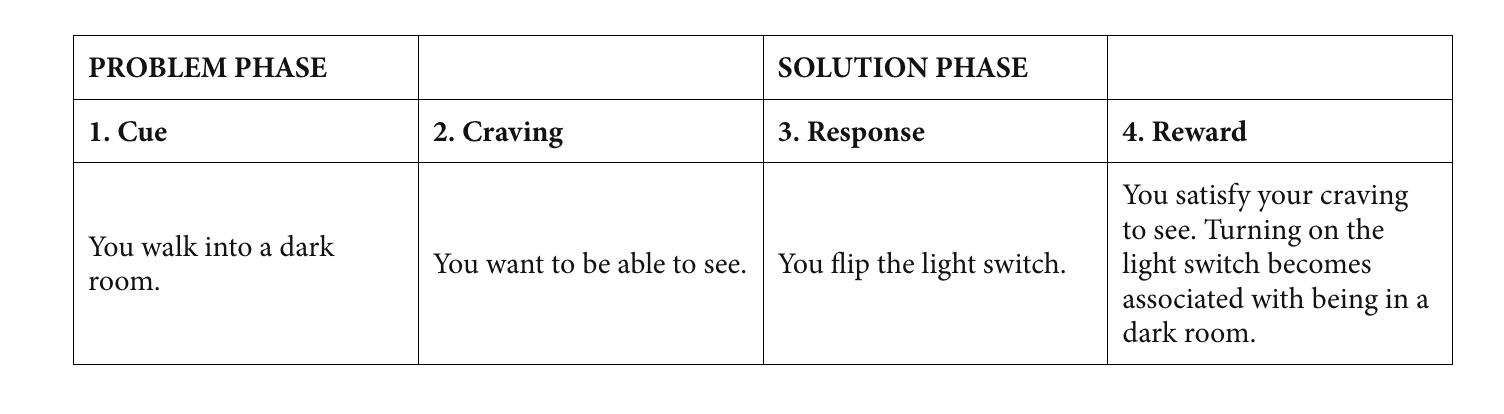

We can split these four steps into two phases: the problem phase and the solution phase. The problem phase includes the cue and the craving, and it is when you realize that something needs to change. The solution phase includes the response and the reward, and it is when you take action and achieve the change you desire.

All behavior is driven by the desire to solve a problem. Sometimes the problem is that you notice something good and you want to obtain it. Sometimes the problem is that you are experiencing pain and you want to relieve it. Either way, the purpose of every habit is to solve the problems you face.

Let’s cover a few examples of what this looks like in real life.

This four-step process is not something that happens occasionally, but rather it is an endless feedback loop that is running and active during every moment you are alive—even now. The brain is continually scanning the environment, predicting what will happen next, trying out different responses, and learning from the results. The entire process is completed in a split second, and we use it again and again without realizing everything that has been packed into the previous moment.

Imagine walking into a dark room and flipping on the light switch. You have performed this simple habit so many times that it occurs without thinking. You proceed through all four stages in the fraction of a second. The urge to act strikes you without thinking.

By the time we become adults, we rarely notice the habits that are running our lives. Most of us never give a second thought to the fact that we tie the same shoe first each morning, or unplug the toaster after each use, or always change into comfortable clothes after getting home from work. After decades of mental programming, we automatically slip into these patterns of thinking and acting.

Where to Go From Here

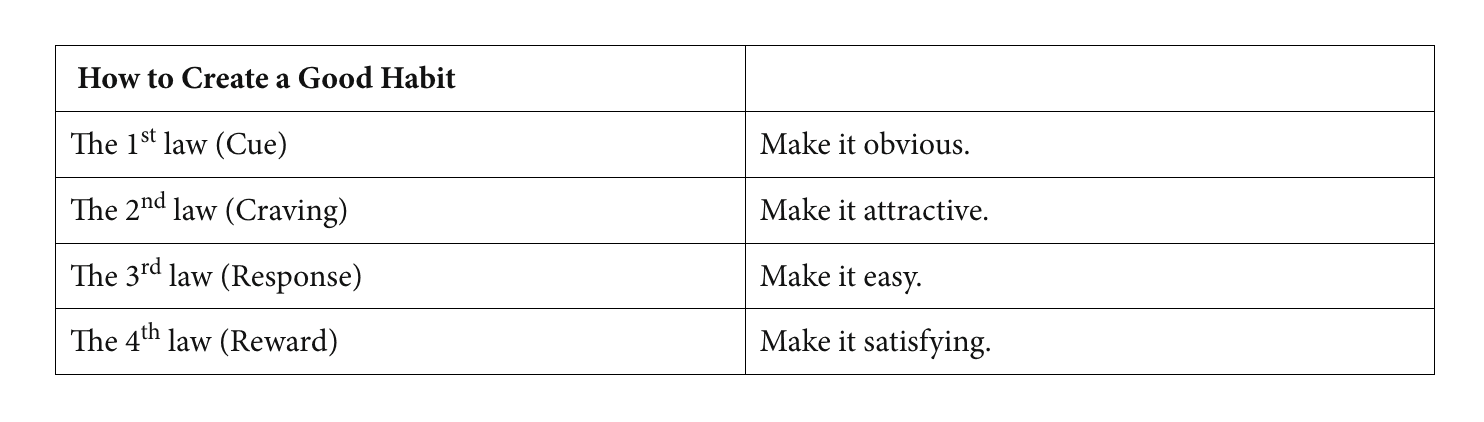

We can transform these four steps into a practical framework that we can use to design good habits and eliminate bad ones.

I refer to this framework as the Four Laws of Behavior Change, and it provides a simple set of rules for creating good habits and breaking bad ones. You can think of each law as a lever that influences human behavior. When the levers are in the right positions, creating good habits is effortless. When they are in the wrong positions, it is nearly impossible.

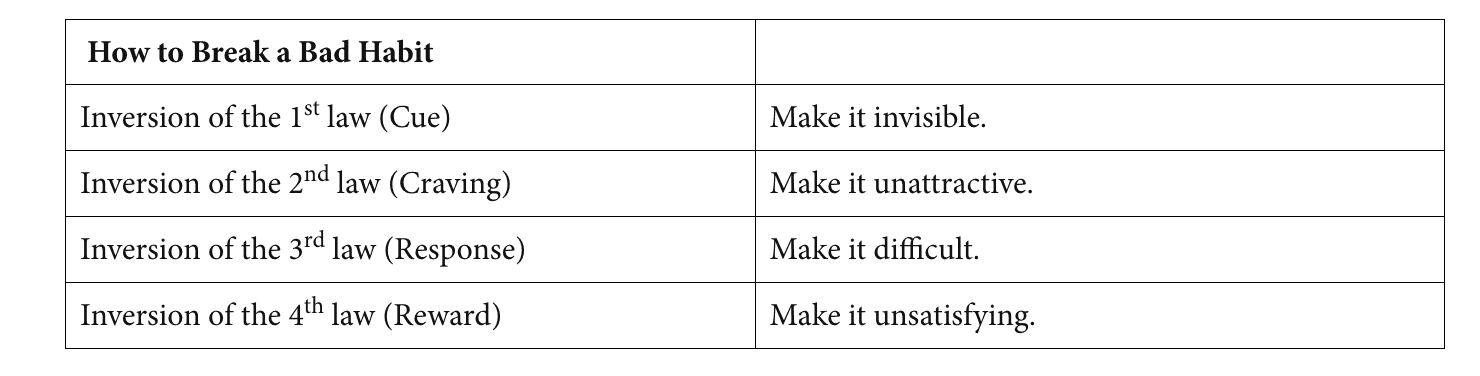

We can invert these laws to learn how to break a bad habit.

Whenever you want to change your behavior, you can simply ask yourself:

How can I make it obvious?

How can I make it attractive?

How can I make it easy?

How can I make it satisfying?

It would be irresponsible for me to claim that these four laws are an exhaustive framework for changing any human behavior, but I think they’re close.

If you have ever wondered, “Why don’t I do what I say I’m going to do? Why don’t I lose the weight or stop smoking or save for retirement or start that side business? Why do I say something is important but never seem to make time for it?” The answers to those questions can be found somewhere in these four laws. The key to creating good habits and breaking bad ones is to understand these fundamental laws and how to alter them to your specifications. Every goal is doomed to fail if it goes against the grain of human nature.

This article is an excerpt from Chapter 3 of my New York Times bestselling book Atomic Habits. Read more here.